Common Probiotic Bacteria Could Help Boost Protection Against Influenza

3D computer-generated rendering of a whole influenza (flu) virus

A newly funded research project might one day lead to the development of a pill or capsule able to boost the effectiveness of traditional vaccines against influenza, which kills as many as 52,000 people and leads to hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations a year in the United States.

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) have received funding to study the concept of using modified strains of probiotic bacteria – that are already part of the human gut microbiome – to stimulate the formation of antibodies against the flu virus in the body’s mucosal membranes. Respiratory viruses like influenza infect the body through mucosal membranes, and the proof-of-concept project will help evaluate whether snippets of influenza proteins – tiny fragments of the virus – could be added to two common bacterial strains to create the antibody response. Antibodies in the mucosal membranes might then complement those created by traditional intramuscular injections to head off flu infection.

The research, supported by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), will study whether or not the harmless bacteria can be successfully modified to carry snippets of a viral coat protein that could stimulate the desired response in mucosal membranes lining the gut. Beyond reducing influenza infection in the general population, improved protection against the flu could have a significant impact on the U.S. military, which wants to provide the best possible protection for its warfighters to reduce possible impacts on readiness and training from influenza outbreaks.

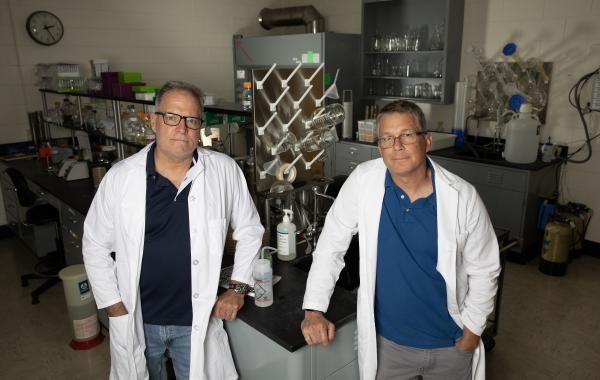

At Georgia Tech, the project is a collaboration between researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) and the Georgia Tech School of Biological Sciences. All of the research at Georgia Tech will be done using BSL-2 facilities designed for this type of study. The award does not include research on animals or humans.

“Ultimately, this could one day make vaccination programs much more effective,” said Michael Farrell, a GTRI principal research scientist. “This isn’t going to be a replacement for flu vaccines as they currently exist, but it could act as an adjuvant – something that’s done in addition to vaccination to increase the overall immune response. To benefit from it, you might take a pill like you do with probiotics now.”

Using Common Probiotic Bacteria as Vehicles

The project will focus on two common probiotic bacteria: Escherichia coli – a gram-negative bacterium better known as E. coli – and Lactococcus lactis, a gram-positive bacterium found in cheese, buttermilk, and other dairy food items. The researchers will attempt to coax the bacteria to express the influenza virus’ Hemagglutinin (HA) receptor protein on their outer cell surface. There, the protein would stimulate an antibody response in the gut mucosal membrane as it passes through the body’s gastrointestinal tract.

“We’re using some well-established probiotic bacteria that have been utilized for dozens of years, are well vetted and safe for humans,” said Brian Hammer, an associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences who specializes in bacterial genetics. “Ultimately, the idea is to use these bacteria as a chassis to create living vaccines, since the body already tolerates them both well.”

Researchers at AFRL and Georgia Tech envision that a single pill or capsule would carry the bacteria into the gastrointestinal tract to provide the necessary antibody stimulation. The bacteria would be modified so they could not reproduce, preventing them from becoming part of the body’s gut microbiome – a diverse collection of bacteria that live in the body and help carry out specific functions, including metabolizing food and modulating the immune system.

“We know the human microbiome is intimately involved in human health and disease, influencing processes in ways that have both positive and negative outcomes for us,” said Richard Agans, senior research biological scientist at the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine (USAFSAM). “Recently, we have started to better understand how the microbiome communicates with our bodies and how we can identify, target, and promote the beneficial aspects. Currently, we are working to determine how to utilize these microbial communities to better protect our warfighters as well as the general public.”

Overcoming Challenges of Manipulating Bacteria

Hammer’s lab specializes in manipulating proteins of organisms such as bacteria and viruses to create novel fusions. Among the techniques available is the new CRISPR-Cas, the gene-editing technology that was the subject of a Nobel Prize in 2020, but other more traditional techniques may also be used to get the influenza surface protein where the researchers want it to be.

Among the challenges ahead is that adding a new component to bacterial organisms can be difficult.

“In general, bacteria have evolved with the genetic components they need to survive,” Farrell explained. “If you add something else, they may just kick it out. It’s very hard to find a neutral location in the bacterial genome where we can stably add new functionality. This is especially true for this effort, in which there will be no cointroduction of antimicrobial resistance markers.”

In addition, the probiotic bacteria strains that are widely used in research as model organisms, or “lab rats,” are adapted to living in laboratory conditions. This project, however, will use natural commensal strains that co-exist in humans. That approach may make it even more challenging to add the appropriate material for expressing the viral proteins on the bacteria cell surfaces, Hammer said.

“We used to perceive that genes could be shuffled around in the bacteria without much effect on them, but we’re learning now that location really matters,” he said. “One of the concerns is that tools that work on the ‘lab rat’ versions of these bacteria will not be as readily accepted by these commensals.”

As part of the project, the researchers will have to show that the addition of the protein doesn’t cause instability in the bacteria, and that the modified bacteria generate the correct response when exposed to human immune cells in culture.

Proof of Concept Could Lead to Broader Vaccine Therapies

Beyond its importance to the military, influenza was chosen to study this adjuvant approach because a number of vaccines exist for this virus, and they have been well studied over the years. If this approach works with influenza, the combination of pill and injection might be useful for vaccines against other respiratory viruses.

“If this is ultimately successful, it could be the first foray into showing that these vehicles, these probiotics, could potentially be scaled up for lots of different therapeutic uses,” said Hammer. “By customizing the cargo, this approach could be rapidly adapted to address new and emerging threats that may arise in the future.”

Project Provides Student Opportunity

The two-year project life was chosen because of the expected difficulty – and because another of its goals is to train a master’s degree student in the bacterial modification techniques being utilized.

The Georgia Tech researchers have chosen an underrepresented minority student who holds an undergraduate degree in biology from Kennesaw State University and has worked in a commercial DNA laboratory. Katrina Lancaster will begin work on this project during fall semester, collaborating with both Hammer and Farrell – and the students and other researchers in their labs.

“This student will have excellent opportunities, not only to learn the skills in the lab and take the coursework, but also to develop a rich network of connections, both in the School of Biological Sciences and at GTRI, that will be helpful in moving forward and advancing their career,” Hammer said. “It’s a really beautiful combination of components for this project.”

The project is funded through the AFRL’s Minority Leaders Research Collaboration Program (ML-RCP).

“Partnering with academic institutions, such as GTRI, presents great opportunities for our team to interact and work with top minds in these fields to develop better outcomes for everyone,” Agans said. “We are especially grateful for the opportunity to mentor and provide opportunities for underrepresented students with STEM aspirations. We are excited to work with GTRI in this endeavor and envision this being just the first step.”

USAFSAM is part of the Air Force Research Laboratory’s 711th Human Performance Wing.

Writer: John Toon (john.toon@gtri.gatech.edu)

GTRI Communications

Georgia Tech Research Institute

Atlanta, Georgia

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit, applied research division of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Founded in 1934 as the Engineering Experiment Station, GTRI has grown to more than 2,900 employees, supporting eight laboratories in over 20 locations around the country and performing more than $940 million of problem-solving research annually for government and industry. GTRI's renowned researchers combine science, engineering, economics, policy, and technical expertise to solve complex problems for the U.S. federal government, state, and industry.

GTRI Researchers Michael Farrell (left) and Brian Hammer (right)