The Unseen Victims of the BP Oil Spill

Kostka BP Oil Spill

On April 20, 2010, an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil rig released a torrent of oil in the seafloor of the Gulf of Mexico, discharging close to 5 million barrels of oil in 87 days. It was the largest accidental oil spill in U.S. history. Six years later, researchers such as the School of Biology’s Joel Kostka continue to study the disaster’s environmental impacts.

Much work has gone into accounting for the spilled oil. We know that 25 percent was recovered by federal response efforts, 5 percent evaporated and 70 percent was left to degrade in environment. Meanwhile, legal proceedings have prevented the release of some key research results and studies continue. But thus far, microbes appear to have degraded the oil quickly in many areas of the Gulf.

Other circumstances mitigated the environmental damage. Because the spill occurred in the deep sea, much of the oil remained away from sensitive coastal habitats. And because of favorable weather conditions in the spring and summer of 2010, much of the ocean-surface oil remained offshore in the northeastern portion of the Gulf. Likewise, the oil did not get entrained in major ocean currents, which would have carried it to other parts of the Gulf or to other oceans.

Unquestionably, some ecosystems were devastated, including deep-ocean corals that have lived for hundreds of years, as well as other seafloor marine dwellers.

Less certain is what happened to the microscopic floating organisms, the plankton, which are the foundation of the massive food webs of the oceans.

Unlike the large animals whose oil-soaked images predictably provoked calls for action among the public, plankton are not visible, much less photogenic. Yet, their well-being has wide repercussions because they comprise the bottom of the food chain in ocean ecosystems. Without plankton, oceans will die.

As the visible signs of the DWH disaster fade, the public may be lulled into assuming that all is fixed and well. In fact, many questions remain unanswered.

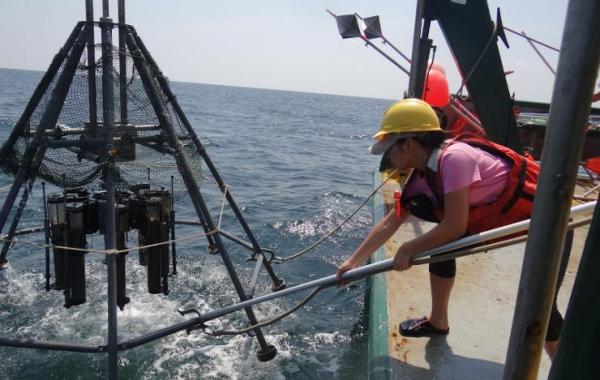

Kostka’s Georgia Tech team is working with the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative to address some of those questions, eventually hoping to enable the development of better spill mitigation and remediation technologies by harnessing the natural processes enabled by the ocean’s smallest organisms.