When Physics Gives Evolution a Leg Up by Breaking One

Genetic mutation may drive evolution, but not all by itself. Physics can be a powerful co-pilot, sometimes even setting the course.

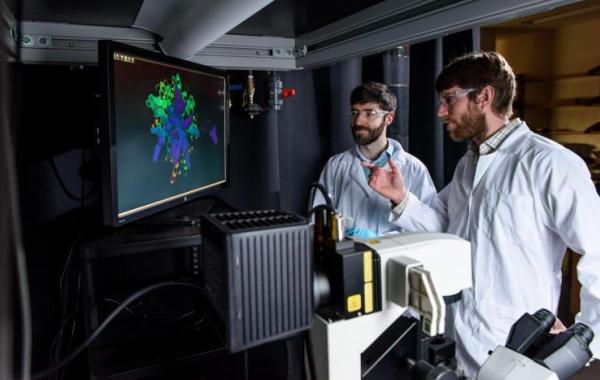

In a new study, physicists and evolutionary biologists at the Georgia Institute of Technology have shown how physical stress may have significantly advanced the evolutionary path from single-cell to multicellular organisms. In experiments with clusters of yeast cells called snowflake yeast, forces in the clusters’ physical structures pushed the snowflakes to evolve.

“The evolution of multicellularity is as much a matter of physics as it is biology,” said biologist Will Ratcliff, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences.

The bigger they are…

Like the first ancestors of multicellular organisms, in this study the snowflake yeast found itself in a conundrum: As it got bigger, physical stresses tore it into smaller pieces. So, how to sustain the growth needed to evolve into a complex multicellular organism?

In the lab, those shear forces played right into evolution’s hands, laying down a track to direct yeast evolution toward bigger, tougher snowflakes.

“In just eight weeks, the snowflake yeast evolved larger, more robust bodies by figuring out soft matter physics that took humans hundreds of years to learn,” said Peter Yunker, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Physics. He and Ratcliff collaborated on the research that documented the evolution and measured the physical properties of mutated snowflake yeast.

They published their results on November 27, 2017, in the journal Nature Physics. The work was funded by the NASA Exobiology program, the National Science Foundation, and a Packard Foundation Fellowship to Ratcliff.

Questions and answers

Here are some questions and answers to illuminate the study and its significance.

But first, some background: Baker’s yeast, which was used in these experiments, is usually a single-cell organism. Yeast cells with a well-known mutation stick together in groups called snowflakes.

That was not the focus of the experiments, but the yeast snowflakes were the starting point in this study on the evolution of multicellularity.

Why is this study significant?

Such a cell cluster like a yeast snowflake is not a well-integrated multicellular organism yet. To make it to even simple multicellularity like that of some algae is a very long evolutionary haul.

“It’s a journey of a thousand steps,” Ratcliff said. “The key change is for this group of cells not to evolve as a gang of single cells but as one multicellular individual.”

In this work, the researchers showed how snowflake yeast took first steps in that direction by evolving more resilient multicellular bodies that sustained growth. The process was mainly driven by physical forces, as the simple snowflakes did not have complex inner biological workings that were capable of being the main drivers.

“This is an amazing example of multicellular adaptation around physical constraints well before the evolution of a cellular developmental program,” Yunker said.

How does this evolution via physical stress work?

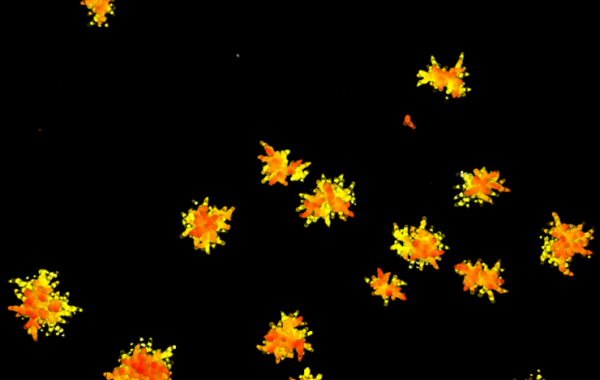

“Yeast snowflakes grew by adding cells end to end to form branches kind of like those of a bush,” Yunker said. “But the branches crowded each other, and the stresses that result made some break off.”

The breakage chopped down the size of individual yeast snowflakes, but after multiple generations, the snowflakes evolved to reduce the crowding of branches by elongating its individual cells.

As a result, the overall snowflakes were less stressed and could grow larger and more robust.

In addition, Georgia Tech researchers discovered that physics made the snowflakes basically have babies. Specifically, the pieces that broke off became propagules that grew into snowflakes of their own.

This reproduction was created by physical force and not by a biological program. Ratcliff published a separate study about the reproduction aspect on October 23, 2017, in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

“Physics does a lot for multicellularity,” Ratcliff said. “It also gives it a lifecycle.” Lifecycle refers to birth, growth, reproduction, and death.

“A consensus is forming that for something to really evolve to multicellularity, very early on, a multicellular lifecycle has to develop.”

Also READ: Evolution, What was the Primordial Stew?

How did the experiments select for these specific adaptations?

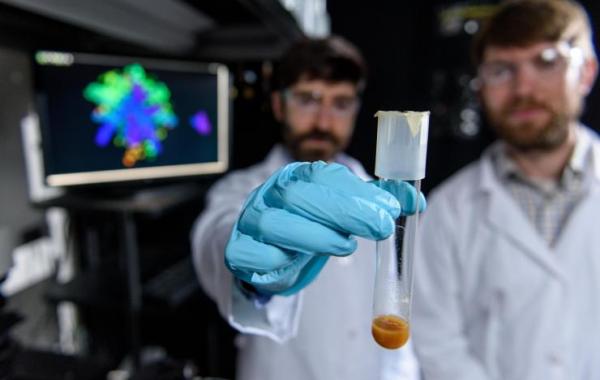

Ratcliff and Yunker streamlined evolution in the lab by creating a consistent selection regime for the yeast snowflakes to evolve in. In this case, they selected for snowflakes that were best at sinking.

The snowflakes that sank better were heavier, because they grew larger than others in the manner described above, giving them more mass. “The clusters that evolved to grow bigger were therefore also heavier,” Ratcliff said.

This experimental selection setup befitted natural evolution, which also had to select for size to arrive at complex multicellular bodies, which are much, much larger than single cells.

Mutation of branches is genetic. Is physics really so important here?

That’s correct: Random genetic mutations resulted in the better, longer branches in some yeast snowflakes giving them a cumulative weight advantage.

But the propagation of the superior snowflake mutations was the result of physical stresses not breaking the snowflakes until they had grown larger.

The pieces that eventually did break off, due purely to physical force, were the propagules. Some of them carried mutations forward that made the new snowflakes even better at sinking.

And that was a critical step in the multicellular evolution.

How was stress corroborated as the cause of snowflakes splitting apart?

The researchers put the material properties of the snowflakes to the test under an atomic force microscope. “We squished the clusters and measured how much force and energy you needed to break them,” Yunker said.

“The physical measurement indicated closely the size the clusters would attain before they broke off a branch due to stress,” Ratcliff said.

Also READ: 'Cavemen' had better mental health genes?

Coauthors of this study were Shane Jacobeen, Jennifer Pentz, Elyes Graba, and Colin G. Brandys of Georgia Tech. The research was funded by the NASA Exobiology program (grant #NNX15AR33G), the National Science Foundation (grant #IOS-1656549), and a Packard Foundation Fellowship. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of those sponsors.