Unlocking the Mystery of Methane Clathrates

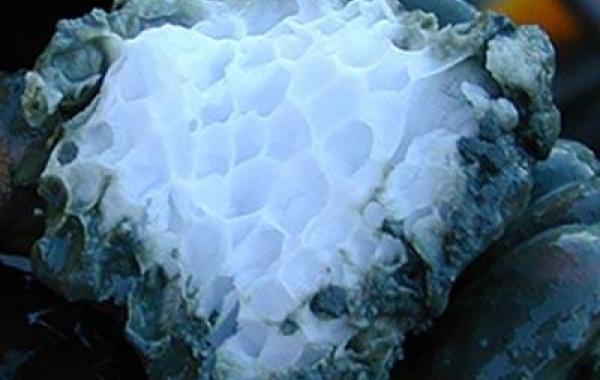

Trillions of cubic feet of natural gas is thought to lie in cold storage within Earth’s permafrost and under its oceans. That gas, however, is trapped within chemical cage-like structures called methane clathrates. Scientists are very interested in these structures, because they may have cousins hidden under the surface of the icy moons in the outer solar system.

Whether the clathrates are on Earth or the Jovian moon Europa, science wants to know: What role did microbes play in their formation and stability? How are they involved when Earthbound clathrates start deteriorating, releasing this greenhouse methane gas into an already-warming global atmosphere? Is that process underway millions of miles from Earth?

An interdisciplinary team of Georgia Tech geo-microbiologists, biochemists, and geo-engineers will have a chance to answer those questions, thanks to a grant from the NASA Exobiology Program that comes with a heady title: Microbial Interactions with Methane Clathrate: Implications for Habitability of Icy Moons. The investigators, which include College of Sciences researchers, will search for DNA blueprints of potential clathrate-binding proteins, will reproduce those proteins in a laboratory, and will test their impact on methane clathrate properties.

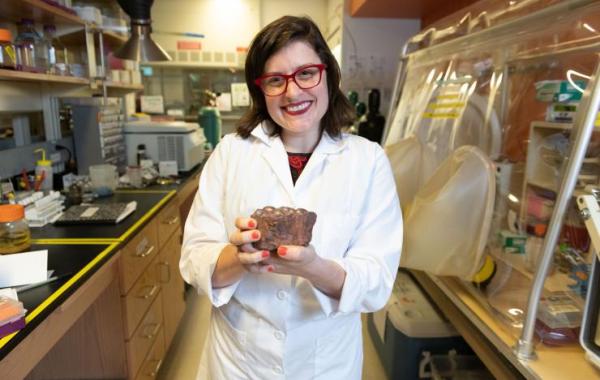

“This is a truly interdisciplinary project to understand how microbial life survives in methane clathrates under the seafloor,” says Jennifer Glass, assistant professor in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. Glass will serve as the team’s principal investigator.

“These deep microbes encode genes that are different from any found on the Earth's surface,” Glass says. “This grant will be one of the first efforts to study the biochemistry of these new biomolecules, and how they affect the structure and properties of methane clathrate. This research is only possible because our Georgia Tech team is uniquely working at the interface between microbial ecology, biochemistry, and geoengineering."

Clathrates are lattice-like structures made of a solid similar to ice. They are buried in polar permafrost and under the world’s oceans, and scientists believe they could hold anywhere from 100,000 to 1 million Tcf (trillion cubic feet) of natural gas. The gas molecules are trapped inside the crystalline structures, but large-scale commercial extraction isn’t available yet. However, plumes of methane have been recorded leaking from Arctic permafrost thanks to global warming. (Methane is already produced via decaying organic matter in landfills, traditional oil and gas exploration, and within the stomachs of domestic livestock.)

Visits from planetary probes, spectroscopy readings, and other research indicate that methane clathrates may exist on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn. They may be part of developing ecosystems. Did microbes interact with those clathrates? Could they be tapped in the search for life in the solar system? Could those gas resources help sustain human habitats on the Jovian moon Europa?

"We are excited to learn more about the fascinating molecules that bind methane ice in this unique environmental niche,” says Raquel Lieberman, professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and one of the methane clathrate team members. “These proteins don’t look like any others known in temperate environments."

In addition to Glass and Lieberman, other team members include research scientist Anton Petrov and Professor Loren Williams, both with the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry; and Sheng Dai, assistant professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Abbie Johnson, an EAS graduate student in the Ocean Science & Engineering Program, will work on the project for her doctoral dissertation.

Glass has a courtesy appointment with the School of Biological Sciences. She also is on the faculty of the Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Biosciences.