Tech researchers team up for advanced materials

By Renay San Miguel

Ask Georgia Tech researchers working with advanced materials for examples, and they give a pop culture reference. Two of them even cite the same reference.

“It’s like The Terminator, liquid metal that then becomes a solid,” says Alberto Fernandez-Nieves, associate professor in the School of Physics.

“Think of The Terminator,” says another School of Physics associate professor, Jennifer Curtis.

Pop culture so effectively appropriates next-level science research, that it comes as no surprise that these scientists first thought of Oscar-winning director James Cameron’s shapeshifting “mimetic polyalloy” assassin from the future in Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

“Or that animated movie, Big Hero 6,” Curtis adds, referring to a 2014 Disney film about nanobots combining to form bigger objects. “We would love to find an original way to create small shapes. And then make them intelligent enough to properly reconfigure in some other way.”

Georgia Tech scientists aim to make those science-fiction scenarios real through collaborative, interdisciplinary research at the Center for the Science and Technology of Advanced Materials and Interfaces (STAMI).

Launched in 2016, STAMI comprises four groups:

- Georgia Tech Polymer Network (GTPN)

- Community for Research on Active Surfaces and Interfaces (CRĀSI, pronounced crazy)

- Soft Matter Incubator (SMI)

Of all those acronyms, COPE’s has been around the longest, since 2003. COPE helped develop the optical technologies that enable flat-screen HDTV to deliver sharper resolutions on any monitor size while consuming less power.

Over the years, COPE has attracted some $84 million in research funding and research-related awards, says Seth Marder, Regents Professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry and COPE’s founding director. That’s because “we were able to create multi-investigator proposals with a very high degree of success,” Marder says.

Because proposals from centers with teams of researchers tend to attract more funding, Marder and colleagues set up STAMI to brew ideas and foster collaboration among researchers across Georgia Tech.

“People who work in advanced materials recognize that collaborative approaches are critical,” Marder says. At COPE and now in STAMI, he adds, “we recognize that if you build the strong human relationships, the strong collaborative scientific relationships will be that much stronger, that much more fun, and it will lead to that much more productivity and the opportunity to do other things.”

The promise of advanced materials

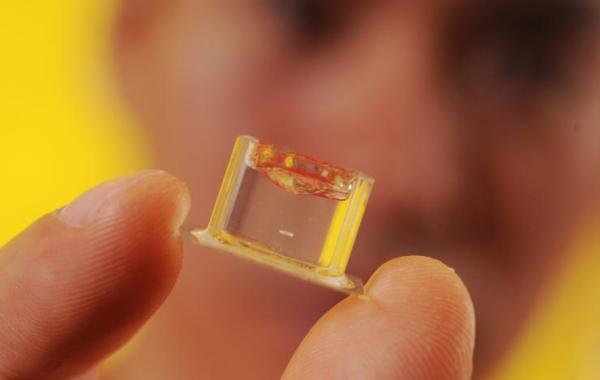

When subjected to stimuli – such as current, light, heat, or chemicals – liquids, foams, gels, liquid crystals, and other substances may respond and change, or even acquire new functions.

The liquid crystal displays (LCDs) and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) in smartphones and TV/computer monitors are organic photonic technologies in action. They are marvelous combinations of thin films, electrolytic gels, and molecules that respond to light and electricity.

Soft matter is anything that can be prodded, poked, folded, warped, or deformed by weak external causes, including heat and mechanical forces. Examples abound but the science around them is relatively young.

Polymers, strings of repeating molecular units, can be natural, like the DNA in cells, or synthetic, like the plastics in houses. Manipulating them can yield stronger construction materials or more effective medical treatments.

Advanced materials can mean progress from healthcare to defense technology and consumer electronics. But getting materials to work together – and allowing users to program, control, and predict their behaviors – is key to realizing the next-generation promises.

COPE: Collaboration before collaborating was cool

It was the spirit of teamwork that first brought Marder to Georgia Tech in 2003, after appointments at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, and the University of Arizona.

He and three others who were focused on optical sciences started COPE shortly after they arrived at Tech. They believed that a center like COPE would help them brainstorm research ideas while increasing their chance of funding.

That teamwork helped Marder ignore temptations to move to other universities. “What kept me at Georgia Tech is the people,” he says. “If you’re fundamentally connected with the people around you, that’s a pretty strong adhesive.”

To that end, Marder became a strong protagonist for COPE’s collaborative propensity. Materials science can involve physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering, and reaching across Tech’s colleges and schools is key. COPE pioneered this approach.

“You’re not just bringing people together to work on a problem; you need the right culture,” says Bernard J. Kippelen, a professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering and current COPE director. “Georgia Tech is uniquely positioned in that respect because interdisciplinary research is part of Georgia Tech’s DNA.”

Research themes exemplify the intrinsic interdisciplinarity:

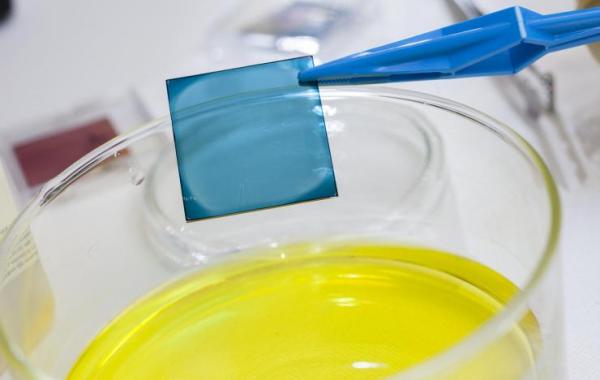

- Organic photovoltaic materials, for solar cell technology

- Flexible organic materials that can go inside or on the body, for medical and sensing applications

- Organic materials to protect sensors and human eyes from laser pulses, of interest to the Defense Department

- Organic materials to enable rapid and safe removal of heat from its source, for computers and consumer electronics

“We focus on organic – carbon-based – materials,” Kippelen says, because they can be processed at room temperature, making manufacturing easier. And because the building blocks are molecules, physical properties can be controlled by changing chemical structure.

“As we study more of these materials to understand why they work, we come across new surprises, new breakthroughs that were not anticipated,” Kippelen says. “It’s the gift that keeps giving.”

GTPN: Pushing polymers for fun and profit, but mostly fun

When John Reynolds joined IBM Research in the late 1970s, scientists had just discovered that plastics can conduct electricity. Until then, “if you wanted high conductivity, you had to get a piece of metal,” says Reynolds, a polymer chemist. “That an organic polymeric material could do that was earth-shattering.” The breakthrough eventually won the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Now Reynolds is a professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry and in the School of Materials Science and Engineering. He also serves as director of GTPN, which launched shortly after he joined Tech in 2012. Reynolds leads with co-directors David Collard, Zhiqun Lin, Elsa Reichmanis, and Paul Russo.

“Georgia Tech and the interdisciplinary atmosphere is why I moved here,” he says. “The walls between colleges and schools here are very low, and that makes Georgia Tech special.”

Reynolds has had a front-row seat for many advances his GTPN colleagues are making in polymer science. He anticipates new materials for applications such as:

- Electrochromism, reversibly changing a material’s color in the presence of an electric field

- Energy savings through separation of hydrocarbon and industrial chemicals using nanoporous membranes

- Energy storage, such as batteries and capacitors to store chemical energy and electrical charge

- Drug and active-molecule release using polymer-modified nanoparticles

When it comes to electrochromic application, Reynolds notes, this technology using polymer gel electrolytes has allowed automakers to eliminate the mechanical switch on rear-view mirrors to suppress blinding high-beam lights from the vehicle behind. Most mirrors now use light sensors and color-changing electrochemical systems to dim that harsh glare.

“That’s a $1 billion a year sales business for a company in Michigan,” Reynolds says.

Yet the most innovative aspect of GTPN, Reynolds says, is its impact on graduate students and researchers at Tech. They’re not just increasing their knowledge of chemistry and physics. “They grow professionally by participating in meetings and seminars, hosting people, and learning how to be professionally social. And they get contacts with companies.”

SMI: Fundamental science from soft matter

Soft matter is described by the University of Edinburgh School of Physics and Astronomy as “all things squishy.”

In that spirit, the School of Physics has been hosting Squishy Physics public events since 2012. Restaurant chefs from Atlanta and beyond prepare foods that illustrate aspects of soft matter: “gelation (jams and jelly), phase transitions (melting chocolate ice cream), emulsions (Hollandaise and other sauces), foams (meringue), and glass formations (confections),” says the Squishy Physics web page.

“In many cases, soft materials are mixtures of phases – solids in liquids, gases in liquids, or liquid-liquid mixtures, for example,” says Fernandez-Nieves, director of SMI. “A polymer gel may be 99% water, but it behaves like a spring. If you push on it, it deforms and retains its shape due to the presence of restoring forces, and thus it’s a solid from that perspective. It’s an elastic material. And it’s made of 99% water and 1% polymer.”

SMI is itself in its early phase, launching in July 2016 to coalesce soft matter research interest at Tech and provide brainstorming opportunities, workshops, and seed grants.

So what exactly is SMI incubating: ideas or specific research projects?

“Both,” Fernandez-Nieves says. “You can use soft materials as models to address interesting questions beyond soft matter.” The holy grail in the field is matter with controllable and predictive qualities. “What do I need to do to make that happen? That’s where fundamental science comes in.”

A recent research paper co-authored by Fernandez-Nieves offers an example of soft matter’s potential. Microgels and polymer networks made of natural fibrin, a blood-clotting protein, self-assemble to form tunnels that could allow healing substances to pass through. The Department of Defense, hoping for battlefield applications, supported part of the research.

SMI is a place “where you can incubate ideas and so they can come to fruition,” Fernandez-Nieves says. “I think of SMI as driven by people with ideas and drive, and the desire to do new things.”

You don’t have to be CRĀSI to study interfaces, but it helps

Since 1978, Odyssey of the Mind has staged global problem-solving competitions for students in kindergarten through college. The competition stresses teamwork. Thinking outside the box isn’t just encouraged; it’s necessary.

At Tech, Jennifer Curtis and Michael Filler, CRĀSI co-directors, are hosts of their own Odyssey of the Mind-style competitions for professors only. The focus is on thinking way outside the box in getting advanced materials – their surfaces, actually – to communicate, work together, and respond to human commands.

These gatherings of the minds are needed, because none of the next-level advances in materials science happens without figuring out surfaces and interfaces, says Filler, an associate professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

“There is an opportunity to target interfaces, the position where materials change from A to B,” he says. “They’re ubiquitous, and they’re really hard to study, because they’re dynamic.”

“The big thing we would love to do is control how smaller objects interact with each other to make programmable, reconfigurable matter,” Curtis says.

The idea of assembling matter is not new. But with the types of assemblies Curtis and Filler are talking about, it might be easier to kill the Terminator. Why?

“We’re just not good enough with the interfaces, programming them and controlling them,” Filler says.

That’s the obstacle CRĀSI wants to topple. Like SMI, CRĀSI also launched in the summer of 2016 to start conversations about possible solutions to tough science problems. So far, CRĀSI has hosted a total of 10 events, mostly Odyssey of the Mind competitions. Curtis and Filler never share the agenda for their meetings because they don’t want any biases to creep into the discussion.

Curtis is pleased with the buy-in from researchers. “There’s a critical mass of people who want to be in the same room to talk science and explore ideas,” she says. “We’re really trying to identify the grand challenge of the next decade.”